The dark Hitchcock movie Sean Connery filmed before Goldfinger

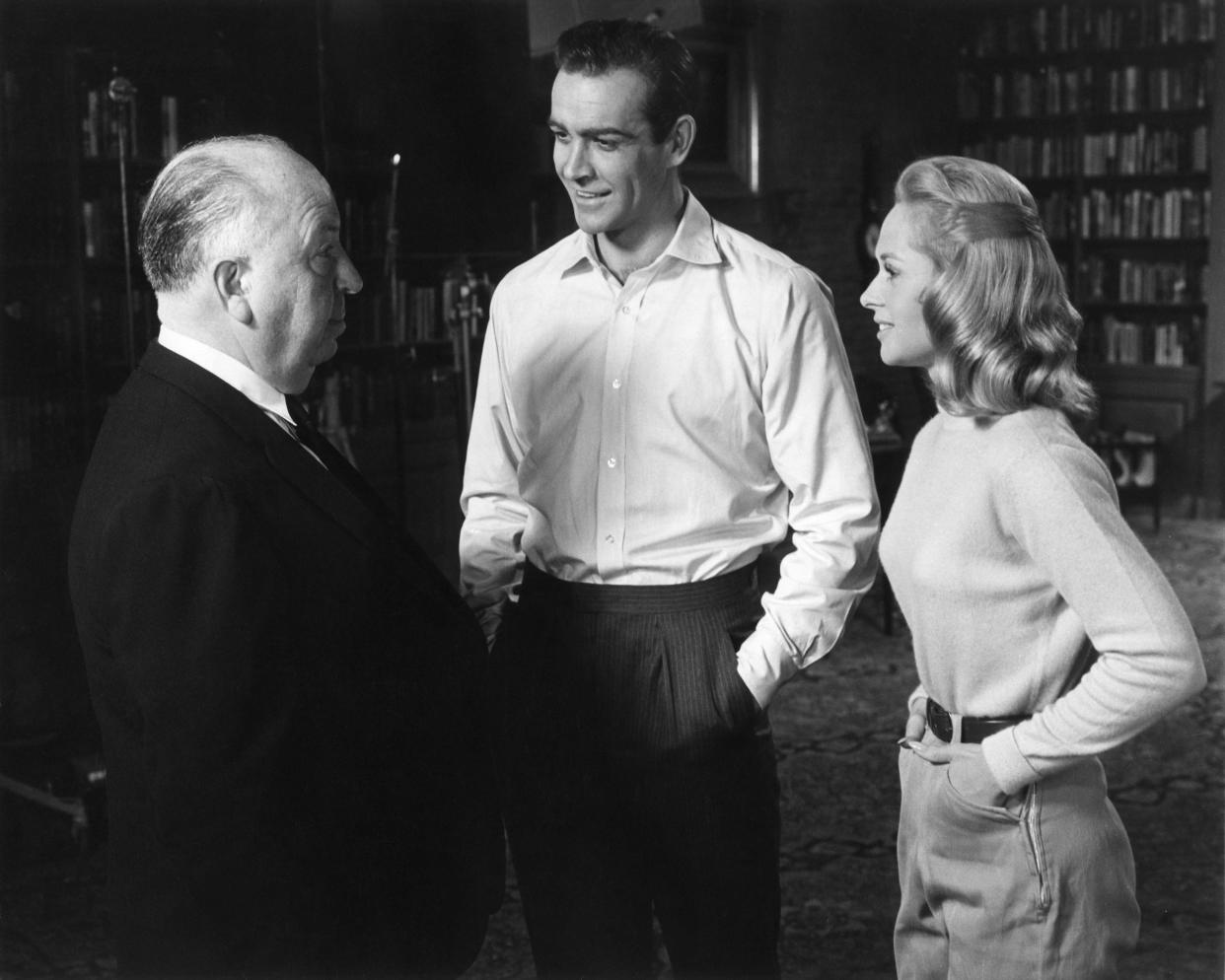

In 1964 Sean Connery’s third James Bond film, Goldfinger, sent him stratospheric. Bond became a global phenomenon, and Connery found himself as famous as 007’s least-favourite band, The Beatles. But just before filming Goldfinger, Connery made a movie directed by Alfred Hitchcock that still surprises his fanbase.

Marnie — which, like Goldfinger, celebrates its 60th anniversary this year — starred Connery as a zoologist who tries to “cure” his wife’s hatred of men. His character is smug, cruel, and arguably a rapist, in a fascinating and problematic film that still splits audiences. But Connery didn’t mind: he was paid $400,000 dollars to work with the Master of Suspense — a whopping eight times his Goldfinger paycheck.

In this extract from my book HITCHOLOGY: A Film-by-Film Guide to the Style and Themes of Alfred Hitchcock, I discuss how ‘Hitch’ used his trademark narrative tropes and formal flourishes — and an unusually unsympathetic role for Connery — to achieve his aims.

Nothing in Hitchcock divides audiences and critics like Marnie. Hitchologist Robin Wood called it “one of Hitchcock’s richest, most fully achieved and mature masterpieces”, while The Guardian journalist Bidisha Mamata passionately condemned it for its “full-on misogyny, rampant woman-blaming and outright abuser apologism.”

It’s possible to appreciate both viewpoints: at best Marnie is a beautiful, surreal examination of complex, fascinating characters (in front of and behind the camera); at worst it’s an overly talky, humourless slog with a morally repugnant ideology. Either way, it remains one of the most intriguing case studies of Hitchcock’s stylistic flourishes and thematic preoccupations, and represents his final dalliance with knotty psychosexual concepts.

Marnie’s very first shot should give you some idea of what to expect. It’s a close-up of a handbag full of stolen cash, but this particular handbag is more than a mere prop. Its carefully-chosen design lends it a visual connotation that must have delighted both the smutty child and the Freudian fanboy within Hitchcock, and to him it would have almost certainly signified feminine mystery: a key theme for the following two hours.

The bag, and the mystery, belong to Marnie Edgar (Tippi Hedren), although we soon discover the loot was pinched by one of her many fake identities, Marion Holland. Notably, this isn’t the first time the theft of a large amount of money from an office by a woman named Marion has kickstarted a Hitchcock plot, and it’s not the only callback to his previous pictures.

Marnie’s aversion to the colour red recalls Gregory Peck’s reaction to seeing wavy lines on white material in Spellbound, and similarly holds the key to a repressed memory at the heart of the film’s psychological riddle. The long tracking move from a wide shot to a dramatically significant close-up, so effectively deployed in Young And Innocent and Notorious, returns here as Hitchcock’s camera zeroes in on the face of a man about to unwittingly cause trouble for Marnie. And Psycho’s climactic exposition dump is back, this time helpfully accompanied by illustrative flashbacks, but still trying to tidy up Hitchcock’s ultimate hot mess in convenient, simplistic fashion.

Read more: Hitchcock

Marnie’s apparent kleptomania and pathological dishonesty appeal to Mark Rutland (Sean Connery), a zoologist who, not coincidentally, has a history of taming wild animals. Mark, wearing arrogant entitlement as comfortably as his tailored suits, is almost as dysfunctional as Marnie, and whether he’s the film’s hero or another of Hitchcock’s smooth, sophisticated villains is the subject of considerable critical debate.

The casting of Mark is key to this ambiguity: fresh off the back of two films playing James Bond, Connery ports over that character’s capacity for brutality but leaves the charm behind. Mark genuinely wants to ‘cure’ Marnie’s crippling inability to enjoy a physical relationship with men (which the film overwhelmingly presents as a problem to be solved), but whether it’s for her benefit or to satisfy his own ego and libido is questionable.

Mark’s own brand of amateur therapy finds its most unsavoury expression in the scene where, having blackmailed Marnie into marriage and grown frustrated by her sexual antipathy towards him, he appears to force himself on her during their honeymoon on a cruise ship. Whether Mark rapes Marnie, and whether the film — and therefore Hitchcock — condones his behaviour is still furiously debated, but it’s worth noting that many of the critical arguments in Mark’s defence are much more linguistically convoluted than those against.

Yet the woman credited with Marnie’s script, Jay Presson Allen, described it as “just a trying marital situation. I did not define it as rape [...] you forgive [Mark].” Obviously it would be too much to expect Hitchcock to clear things up: in a possible attempt to pre-emptively absolve himself of responsibility, he refers to the episode in the film’s trailer, claiming with inappropriate drollery that “I’m not certain I understand this scene.”

In the course of describing its troublesome content, the scene generates some unique visual shorthand. As the camera pans away from the unhappy couple to a view of the ocean through a porthole, the familiar cliché of crashing waves signifying unbridled passion is absent. Instead, the eerie stillness of a dead calm sea speaks quiet volumes. And the ship itself becomes a grim motif: the vessel where Marnie’s ordeal takes place has a counterpart docked in a harbour at the end of the street where she grew up.

Given what we eventually discover about her past, the ship that looms over her childhood home signifies the incident that clouds her entire life. When we finally see that formative traumatic event, Hitchcock introduces it with a variation on the contrazoom shot he made famous in Vertigo. Here, it performs a different function: a visual representation of the past being pulled forcibly into the present.

Hitchcock’s visual style in Marnie is almost as controversial as the rest of the film. Several shots are gratingly artificial-looking due to obvious rear projection or poor matte work. And this isn’t just from a modern perspective; contemporary audiences and critics also pulled the film up on its unconvincing optical effects. But Hitch had been using such processes since his silent days, so why don’t they work here? Some Hitchologists surmise that he lost interest in the film after falling out with Tippi Hedren mid-shoot, while others claim the foregrounded artifice is intentional: a deliberate effort to visualise Marnie’s disconnect from the world.

At least one scene in particular is a classic episode in Hitchcockian suspense: Marnie robbing the Rutland safe on one side of a wide shot, while on the other — separated by a wall and unseen by Marnie, but visible to us — a cleaner goes about her business, sure to discover the crime any minute. It’s one of the film’s few moments of fun (Hitch even caps the scene with a punchline), but it also works to manipulate audience identification. We want Marnie to get away with it, just like we wanted Marion’s car to sink into the swamp in Psycho when it got stuck halfway in. Hitchcock’s ability to make us sympathise with his criminals is one of his most mischievous skills, but who the real criminal is in Marnie is still one of its many hot topics. You suspect Hitchcock wouldn’t have it any other way.

HITCHOLOGY is out now in paperback and ebook from Amazon and other retailers.

Marnie is streaming on NOW with a Sky Cinema Membership.