‘A lot of stereotypes to break’: Children’s Inquiry musical explores life in care in Britain

When theatre-makers Matt Woodhead and Helen Monks gathered with a small group of children in a theatre in Essex five years ago, the plan was simple: discuss the care system.

Woodhead and Monks are co-directors of Lung Theatre, a company that has made a name for itself by tackling weighty subjects, such as the Chilcot inquiry, housing evictions and, most recently, the spate of self-inflicted deaths at Woodhill HMP, that are often investigative verbatim pieces.

At the weekly meetings held at the Queen’s Theatre in Hornchurch, Essex, the four children who the pair talked with began to reveal stories: one had been through eight different homes, another chose to stay with her foster family.

They provided the basis of the Children’s Inquiry, a sprawling musical about life in care and the history of the labyrinthine system that more than 80,000 British young people now find themselves in.

“The young people talked about being impacted by a ‘system’ but not necessarily being able to name it or describe how it acts,” says Monks. “So trying to investigate it together became the modus operandi of the group.”

The play doesn’t just tell the children’s story, it weaves 150 years of care system history through their narrative (it’s “like Matilda meets Hamilton but set in a community centre in Essex” is how one of the team described the Children’s Inquiry).

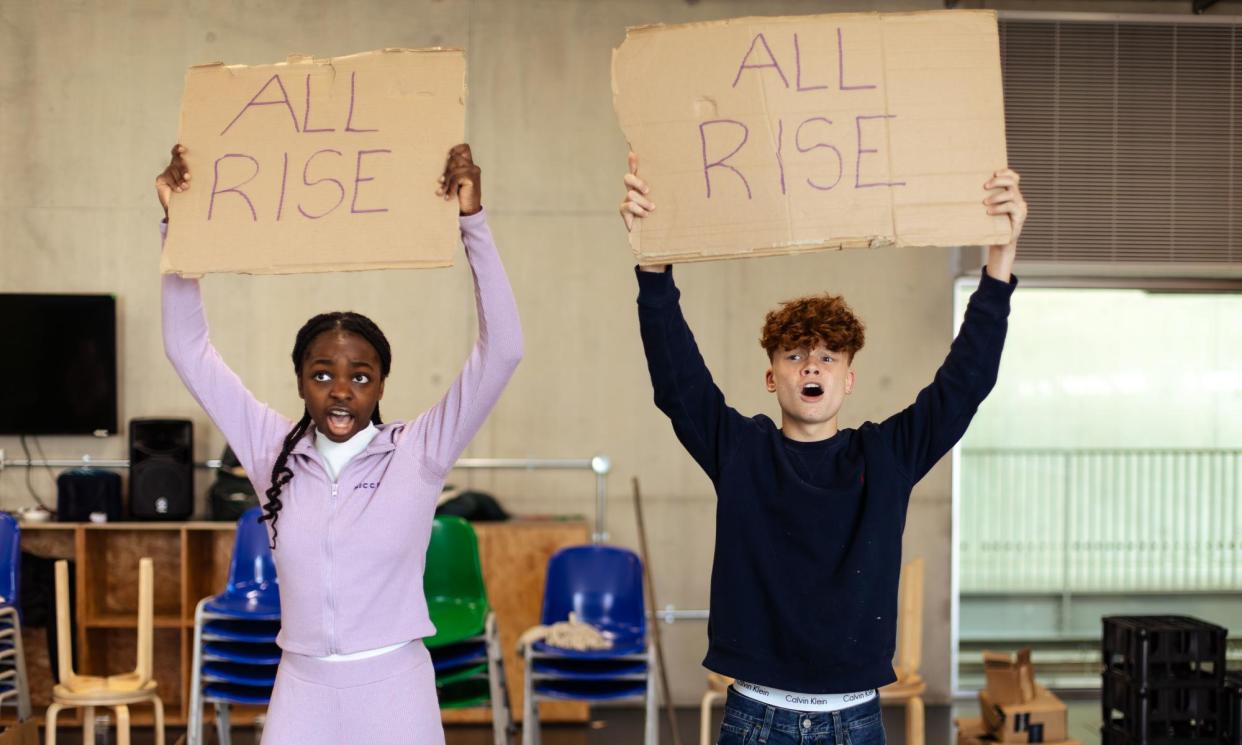

The cast, who are all children, play historical figures such as Amelia Dyer, the nightmarish 19th-century figure who fostered (or “farmed”) infants, received payment for doing so and then murdered them over a 30-year period.

Despite the heavy subject matter, there’s a lightness to the Children’s Inquiry.

The songs are huge symphonic pop tracks written by Owen Crouch and sung by vocalists, including Clem Douglas, who is best known for her work with drum’n’bass producers Chase and Status.

None of the music team have backgrounds in musical theatre and the combination of their pop sensibilities with lyrics that allude to life in the care system creates something genuinely unique and, often, incredibly catchy.

“If you’re in care / it’s a long round but just hold on / you’ll get there just know that you’re not alone,” are the lyrics of one song, which are typical of the hopeful tone.

“It’s difficult to open up your past to people you’ve never met, it is challenging in a way,” says Tom Hume-Steer, 18, who worked with Lung. “The songs are a vibe but when you listen to them they’re actually quite deep.”

“There are a lot of stereotypes that we need to break,” says Tamara Browne, 18, another of the young people the team worked with. “It’s not like you’re in prison, they’re trying to help you and the path might be straighter.”

Usually, says Monks, there’s a satisfying resolution to the work: it’s often obvious where the faults and the blame lie. With the Children’s Inquiry the denouement is less clear; care is more complicated.

Unlike some of the other subjects they’ve tackled, the care system has changed dozens of times. Its rules and regulations are nearly always reactionary, with changes prompted by another shocking death – like that of Dennis O’Neill who was starved and then beaten to death by his foster father in 1945.

“When the Dennis O’Neill case happened the judge said that it ‘should never happen again’,” says Monks “That’s been a repeated refrain, and it continues to happen; there are a huge number of young people who are killed by a known adult.”

The latest government intervention came in 2022, with the Josh MacAlister report into care which called for a five-year, £2.6bn programme to reform a system that is under “extreme stress”.

Despite the cyclical nature of the care debate, Lung and the young people are hopeful. “Unlike our other productions, where it’s like: this thing is really bad: the end,” jokes Monks. “Change is possible but it’s on all of us.”

The Children’s Inquiry runs 8 July to 3 August at the Southwark Playhouse