'You will find your people. We are out here': Columbia resident on then, now of LGBTQ acceptance

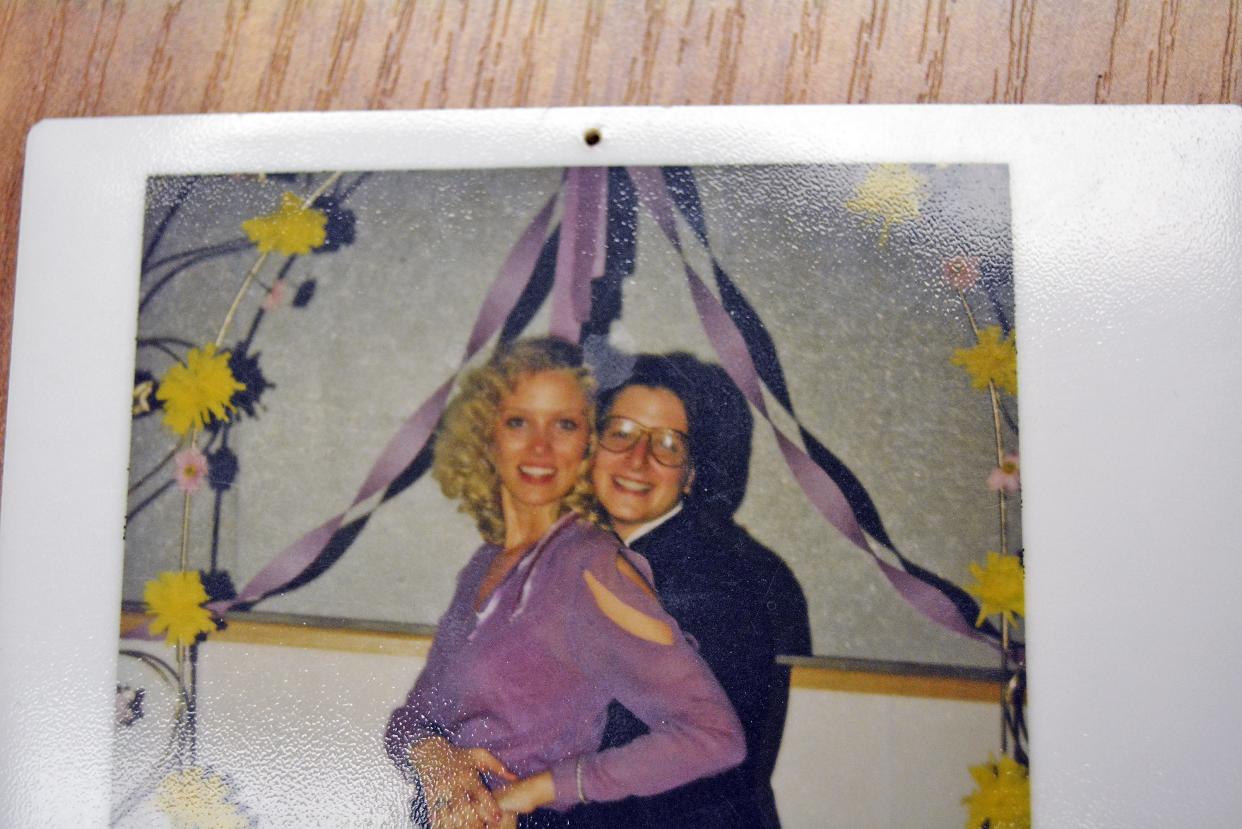

Carrie Barnett in 1978 was a freshman at Stephens College and had heard the murmurings that there possibly was going to be a queer prom held somewhere at the University of Missouri.

Those rumors were accurate, and so, after shopping at a vintage clothing store in downtown Columbia, Barnett put on her tuxedo with tails, walked to the MU campus with her Stephens College roommate — they went as friends — and danced at the queer prom.

Exactly where the event was on the MU campus is lost to the ether for Barnett, who said visiting MU was a rare occurrence during her time at Stephens. There were roughly a dozen visits, she said.

"I remember being totally thrilled about it," she said about the queer prom, adding she also would wear the tuxedo she bought to dances at Stephens. "The dances there were not necessarily queer, but we were, so then they were, even though Stephens in the 1970s was not hip to the queer scene at all. They tried to shut us down a whole lot."

The Tribune, in recognition of the Mid-MO PrideFest, has worked to take down oral histories, however brief, of LGBTQ life in Columbia dating back 40-50 years and how acceptance of those with LGBTQ identities has progressed in the community.

While Barnett mostly was in Columbia for her college years, she still has gotten to see the then and now of acceptance in Columbia. She moved back to Columbia from Chicago five years ago.

"I think I was ready to change the pace of my life," Barnett said. "Chicago, I loved Chicago and I lived a block from Lake Michigan. But there were the taxes, traffic and I work from home, so it didn't matter where I work. I have a really good friend who lives here and teaches at Stephens, so I came back to be here."

During Barnett's first stint in Columbia in the late '70s and early '80s, the only way a person could learn about gay culture or bars was through grapevine whispers. One of those bars was a Quonset hut on Mexico Gravel Road known as Zazoos. She went here in the year after she graduated, but now as a Stephens employee.

"I had a car by then. I remember piling people in the car and driving out there. There was nothing north of Interstate 70 then. Columbia was half the size it is now. There was no GPS or Mapquest. Gaydar took us there, I don't know," Barnett said with a laugh, adding there was a $5 membership fee because the place likely didn't have a liquor license. "So, they had to be a membership club. It was pretty big. There was all this seating and tables, a dance floor and a bar. We would go there and just dance and dance and dance."

Making no apologies

Barnett was unapologetic about her identity as a lesbian at Stephens, even in the face of the homophobia and harassment she faced from other students and faculty.

"When I came to college I knew I was queer, but I didn't understand there was a culture," Barnett said, adding that even though being LGBTQ at the time still was classified as a mental illness, that still was reassuring because that meant there were other people out there like her. "It's kind of a strange thing. I think being (at Stephens) was thrilling. To see other people and to be so young and to start to get a glimmer of an idea of (LGBTQ) culture and community."

Even so, Barnett had to contend with "painful and confusing" rumors of what were false sexual assault allegations made by a group of other Stephens students.

"The rumor was that I was inviting women to my room under the guise of having men from Mizzou there and then I would get them drunk and have sex with them. They were essentially calling me a rapist. It was unbelievable to me," Barnett said, adding she requested to have the accusers say all this directly to her face in a meeting she had with the dean.

"They couldn't because it wasn't true and they just wanted (the dean) to be their hammer," she said. "I wish I kept a journal then because it went on for weeks where (the dean) was trying to control me. I was the head of the Warehouse Theater, which was a student run organization and she said, 'Well you have so much power, you have to consider yourself like a faculty member. I remember saying to her, 'I'm 19.'

"There was nothing she could do but harass me and I think they made me go see the psychologist at school."

After consulting with her brother, who is a lawyer, he advised her to tell the dean that she would take her story to Newsweek and Time Magazine. After doing so, the harassment and rumors were stopped.

"Why should I have to threaten a dean to stop harassing me because these students would not meet me face to face and had no true things to say? It was unpleasant," Barnett said.

A compromise that was developed was in-dorm meetings with incoming freshman about campus life.

"They would talk about things to get used to as a freshman and how to go to dinner and all those basic things. 'And there are some women here who have a different idea about sexuality, but you do not have to do what they say,' essentially. Isn't that bananas? That was the '70s at Stephens," Barnett said.

Last year, when Barnett was watching the Mid-MO PrideFest's inaugural parade, she saw a contingent from Stephens College who were just as unapologetic about their identities as she was in the '70s.

"It was overwhelming and emotional to me to remember what it was like then. I jumped in and asked if I could march with them for a block," Barnett said, adding she received an enthusiastic yes. "I think the parade here is so sweet and lovely and I really enjoyed being there last year."

A place for 'People Like Us'

Barnett was a theater major at Stephens, graduating in 1982. She stuck around in Columbia for about year afterward to work at the Assembly Hall at Stephens, which was demolished a decade ago. After her extra year in Columbia, she went to graduate school in Wisconsin.

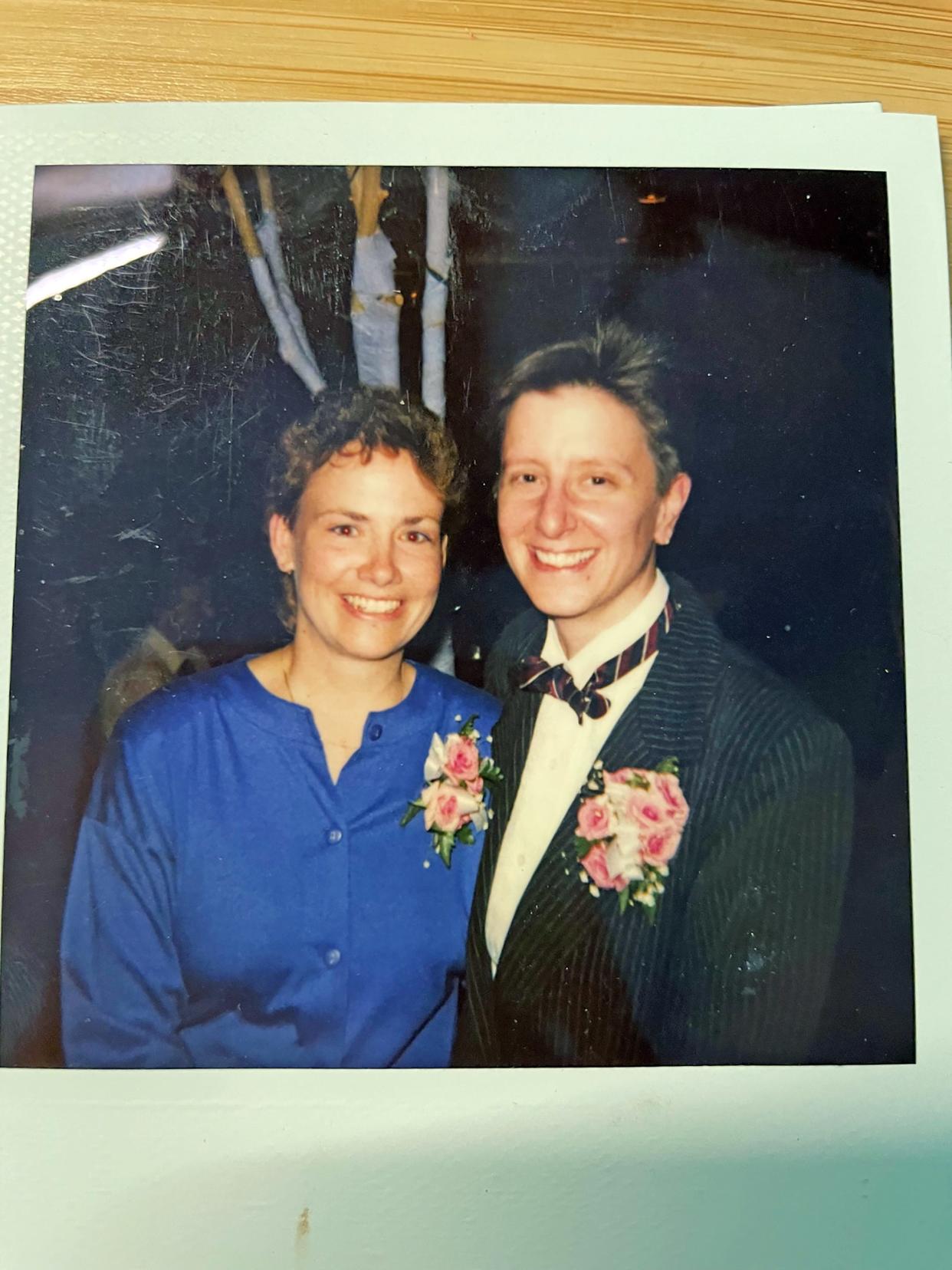

Her life path then led her to a career in Chicago where she worked in the theater industry for about three years. By 1988 she and her gay male friend and business partner Brett Shingledecker opened People Likes Us Books, a LGBTQ bookstore. It remained open for about a decade.

"I was pretty immersed in the community at that point. It was weird how it was sort of scandalous and people would ask us if we were really gay," Barnett said, smiling. "... We mixed our fiction. We had gay and lesbian fiction all on one bookshelf on one wall. People were aghast at that.

"Any time people came in, they would say 'People like us. It's either a gay bookstore or a young Republican's club.' Which were you hoping for? People came in and would say the most random things to us," she said.

This business venture eventually would lead to Barnett and Shingledecker's induction into Chicago's LGBTQ Hall of Fame in 1998.

"My mom was there. It was really cool. I was so excited she got to come. She cried. It was so sweet," Barnett said.

The bookstore would welcome major names in LGBTQ authorship and history through its doors, such as Harry Hay, founding member of the Mattachine Society; English writer and humorist Quentin Crisp; comic artist Alison Bechdel; Olympic diver Greg Louganis; and author Armistead Maupin, among others.

Barnett has an original Bechdel comic, which is the sixth entry in Bechdel's "Essential Dykes to Watch Out For" collection.

When Louganis was preparing to come out, there already was knowledge among the LGBTQ community about what was coming.

"So, we ordered cases of his book. Most other places ordered two copies. We lobbied to have him appear at the store and he agreed," Barnett said, adding while he did end up making an appearance at the Barnes and Noble one-half mile away the night before, the event at People Like Us had greater attendance. "That was quite gratifying."

Barnett was part of the growth of LGBTQ indie bookstores in the U.S. in the '80s and '90s and their unfortunate shrinkage due to the advent of big box bookstores like Barnes and Noble. She is pleased there now is a seeming resurgence of LGBTQ bookstores.

"Is there a place for queer bookstores now? I think the answer always is yes, but then it also is really good to be in a place with a store like Skylark (Bookshop)," she said.

Changing moods, changing laws

When Barnett moved back to Columbia from Chicago five years ago one of her earliest questions was to ask a date about where the city's LGBTQ community congregates. In Chicago, not only from running the bookstore, there was community in bars and gyms and other locations frequented by those in the LGBTQ community.

"I was thinking she would say, 'Join this, do that,' but she said, 'Well, we are everywhere here,'" Barnett said. "Yeah, we are everywhere, everywhere else, but where is the community? And she said it isn't like that in Columbia because everybody is so accepting.

"It's a statement that really surprised me having been in the Chicago community. As big as Chicago is, there still was a community and organizations and ways to hang out with people. The Center Project is doing that a little here," she said.

While Columbia is very accepting, that doesn't mean the rest of state is, and certainly not in the Missouri General Assembly, Barnett said.

"I was walking by the library home in a 'Protect Trans Kids' T-Shirt and somebody pulled their car over and said 'I love your T-shirt,'" she said. "There is so much more acceptance, but at the same time, the government is staging this horrific hatred campaign in the form of anti-trans legislation and all these other things.

"It feels better because people are more open, but then it feels worse because back in the day nobody accepted us and we flew under the radar and we were tilting against the windmills to get acceptance. It feels pretty horrifying to live in a state where the government is so dead set discriminating against a small group of people who are just trying to be themselves."

Even with this, Barnett still feels empowered in coming back to Columbia and Missouri to reclaim space and understand it in a different way.

"There are so many of us who are undeniably who we are and willing to risk the dangers of living that life. Ultimately, it has a resulted in a country where queer people can get married," Barnett said, adding this is not something she thought she would see in her lifetime and that while marriage isn't for her, she understands how important it is for others. She expressed wishes that organizations like Lambda Legal had put as strident a focus on trans issues dating back 20-plus years as it had on marriage equality.

More: Smaller community Pride events more important than ever, say Mid-MO PrideFest headliners

While there is more representation in media of LGBTQ identities, internalized hatred still happens for those in the community.

"People are still scared, especially with government judging us so harshly. You just have to be who you are and trust that you will find your people because we are out here," is the advice Barnett has for younger generations. "I am really proud to have been part of the culture and creating the culture and doing it scared. Opening the bookstore. Being so public. It all paid off in a lot of ways for me.

"We are always impacting the generation that follows. It's exciting to see Gen Z being who they are now and to see that as a continuum. I guess I am glad to have been a small part of the continuum of queer liberation."

More: How has Columbia LGBTQ acceptance changed in 40 years? Arch and Column regulars share stories

Charles Dunlap covers local government, community stories and other general subjects for the Tribune. You can reach him at cdunlap@columbiatribune.com or @CD_CDT on Twitter. Subscribe to support vital local journalism.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Columbia resident witness to then and now of LGBTQ acceptance