Pick-up Schwitts

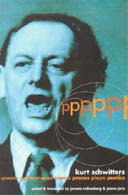

PPPPPP: Poems, Performance, Pieces, Proses, Plays, Poetics

by Kurt Schwitters, edited and translated by Jerome Rothenberg & Pierre Joris

262pp, Exact Change, £10.95

"This is not dirt", the inky-fingered photographer Julia Margaret Cameron is supposed to have exclaimed to the red-shirted Garibaldi, who mistook her for a beggar while visiting England in the spring of 1864, "but art!" It's the kind of claim one might wish to make for oneself, of course, while arranging one's literal or metaphorical fingernail parings, or serving up burnt scrambled eggs. It's certainly the kind of claim Kurt Schwitters might have made for himself.

Schwitters was arguably the last century's greatest connoisseur of rubbish - of ejecta, dejecta, and detritus. Where the century's other great assembler of junk, Joseph Cornell, harnessed and contained his compulsions in his beautiful little hand-made boxes, Schwitters's obsession was unruly and extreme. He pasted words together to make drawings, used pictures to make sentences, and made sculptures from anything at all.

Performer, printer, painter, poet, designer, architect and essayist, he was a polyartist, a Dadaist, and the self-proclaimed founder of the movement or style or method he called Merz (derived either from the German verb ausmerzen, meaning the process of discarding, or merely a filched fragment from the word Kommerzbank, but either way a word and an idea which gave Schwitters the perfect excuse to do whatever he wanted and pass if off as art.

Like all those other great early 20th-century virtuosi of subversion - Marinetti, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Duchamp - Schwitters was extremely businesslike in his disorganisation. According to Hans Richter, "When he was not writing poetry, he was pasting up collages. When he was not pasting, he was building his column, washing his feet in the same water as his guinea pigs ... feeding the tortoise in the rarely used bathtub, declaiming, drawing, printing ... and in the midst of all this he never forgot, wherever he went, to pick up discarded rubbish and store it in his pockets."

Schwitters was born in Hannover in 1887. He studied art, trained as a draughtsman, worked as a commercial artist, founded his own advertising agency, and took on commissions for Hanover City Council. At home, in his parent's house, he started to build the work for which he became renowned: a sculptural column, his Merzbau, a tower-cum-collage, which he called his "monument to Dada", a "cathedral of erotic misery" and, rather more prosaically, "an abstract sculpture into which people can go".

He left Germany in 1937 after Hitler's "Degenerate Art" exhibition displayed the work of the insane alongside work by contemporary German artists, including Schwitters. Fearing for the future, Schwitters went to live in Lysaker, near Oslo, in Norway, where he painted portraits and landscapes for tourists.

In 1940 he travelled to England, where he was interned as an enemy alien; after his release he lived in London before moving to Ambleside, where he died in 1948. He never stopped working: his third and final Merzbau, which he was building in the Lake District, remained unfinished at his death. Schwitters wrote in German, English and Norwegian and for those without access to the five volumes of his collected works, Das literarische Werk, which is probably most of us, Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris offer in their PPPPPP a useful selection of the poetry and prose.

What is pleasing and surprising is that just about everything in Schwitters's essays makes sense and demands assent. There's hardly a single obfuscation or idiocy. Pondering the relationship between his art and the times, for example, he writes that after the first world war, "Everything was in ruins anyway, and something new had to be won from all these shards. That is Merz." He notes, in "The Artists' Right to Self-Determination", that "Merz poetry is abstract. In analogy with Merz painting, it uses as given parts complete sentences from newspapers, billboards, catalogues, conversations, etcetera, with or without changes."

Explaining his work in various mediums and forms he writes: "The reason for it was not so much a desire for a widening of the scope of my work, but rather the endeavour to be an artist and not a specialist in one genre."

So far so good. The problem comes with the poetry. Experimental poetry often appears to be a form of autoeroticism, a series of gleets and effusions. In refusing traditional restraints it makes its own peculiar restraints, or fetishes. Determined to achieve total, uninhibited self-expression, it becomes mute and barren. So what you get, unexpectedly, from Schwitters the poet, undoubtedly a great collagist and a provocative artist, is this sort of thing:

Wound roses roses bleed

Wound colossus wound wound

Roses languish languish roses

Torrid wound torrid torrid

Languish roses languish languish

("Wound roses roses bleed").

Merz? Or just rubbish?

As a poet Schwitters is probably best known for two works, "An Anna Blume", "the best known and most popular German poem of the 1920s", according to Rothenberg and Joris, and "Ur Sonata", his 35-minute long performance poem, which according to the editors, "is to sound poetry what Joyce's Ulysses is to the 20th-century novel". The "Ur Sonata" begins: "Fümms bö wö tää zää Uu". "An Anna Blume" is probably to be preferred, if only because it does not refuse or evade the basic human responsibility of the fully socialised adult, which is to communicate rather than merely to show off:

Does thou know it, Anna,

Does thou allready know it?

One can also read thee from behind,

And thou, thou most glorious of all,

Thou art from the back, as from the front:

A-N-N-A.

This image of a reversible lady is much more disturbing than any of Schwitters's mouth-music. As he puts it himself in his poem "Premonitions": "A concrete pigeon in the hand is worth two abstract sparrows on the roof."

Ian Sansom's novel, Ringroad, is to be published by Fourth Estate next year.