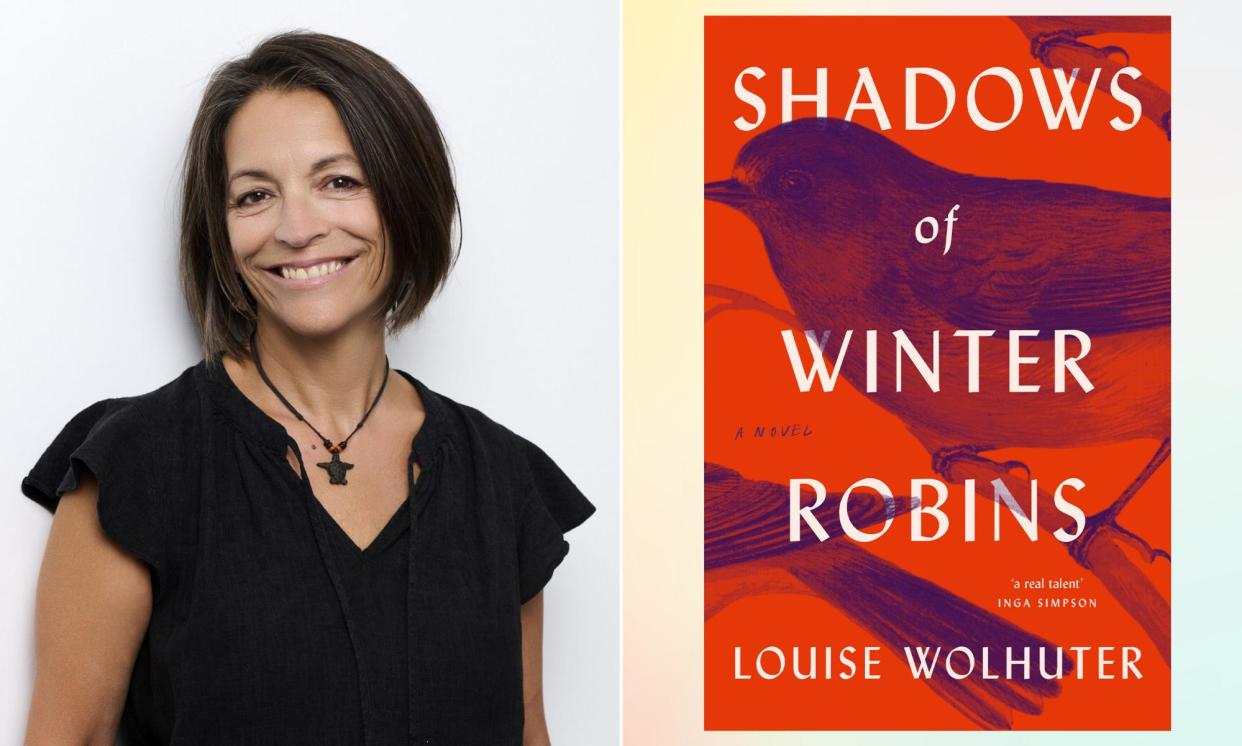

Shadows of Winter Robins by Louise Wolhuter review – a masterful mystery that keeps you guessing

When Winter Robins’ mother, Nancy, dies, she leaves behind Winter and her twin brother, Four, and the story-filled joy of their childhood is dampened with grief. Their father, Lew, loses himself to a sorrow that is “immediate and blanketed everything”. Unable to care for – or even acknowledge – his young children, Lew uproots them from the familiar chill of the north of England to the dry outback of Australia, to live with their mother’s family: people they have never met.

This is where Louise Wolhuter’s second novel starts but it flits between the past and the present – and when we meet Winter as an adult, she’s in mandated therapy. Something dramatic has happened to get her there but she’s playing her cards close to her chest and we must wait for the mystery and twists to unfurl. The therapist has to wait too: “I lie awake at night digging deep for honest answers to her questions,” Winter reflects in her journal early on, “but they are not answers I will give her.”

Related: ‘Radical’, ‘a headrush’, ‘insanely clever’: the best Australian books out in July

This is a book that requires you to pay attention: every detail seems important, just as every member of Winter’s Australian family seems to be hiding something. Dog – her uncle – arrives unexpectedly in England to collect Winter and Four, and is generous and easy-going. “We all liked him,” Winter writes. “Right away and from the beginning.”

But in Australia it becomes clear that Dog’s gentle manner hasn’t done him any favours at home.

The patriarch is Harry, Winter’s grandfather: an imposing outback type as well as a publicly admired painter. But while he seems affable and larger than life, he is quick to reveal an unforgiving streak that leaves his grown son increasingly downtrodden, and the assorted household – including Winter’s grandmother Mo, and Esther, who lives nearby with her young son, Gabe, and works as Harry’s housekeeper – locked under his control.

It’s Gabe who initiates Winter into the mysterious world lying just below the surface of the adults. Their friendship is a refuge, forged from simple childhood secrets, as they try to unfurl the tangled threads that knot this ensemble together. Winter is an old soul and she notices everything; there’s something almost birdlike about the way that she collects details, like the phrase she borrows from Dog: “If two people are in a lift, mate, everyone knows who farted.”

Unnoticed, Winter and Gabe spy on the adults around them. They’re occasionally brought into the fold – when Mo teaches Winter how to play the piano, or when Dog takes Gabe out on to the boat – but for the most part they watch from beneath window ledges and behind trees, trying to make sense of the muses who come and go from Harry’s studio, or the increasingly ill-matched girlfriends Dog brings home to provoke his father. These moments hint at a dangerous world that is both perilously close and just out of reach.

Winter describes one of Harry’s paintings as a “riotous soup of colour-reds and rusts and all the orange of homemade marmalade with bright whites dotted here and there, and chocolate-brown scratches like ribs, deliberate and purposeful”. She might well be talking about the novel itself here, an array of parts and tantalising scratches of information that misdirects as much as it reveals. Readers are given just enough to keep them wondering how all these characters are connected and what past traumas they’ve tried to bury. We learn of hidden relationships and alliances, family secrets and possible crimes. As the layers start to come together it becomes clear how violence has a pull over everyone, fracturing relationships and exposing hard truths.

Wolhuter is clever, predicting where readers’ minds will travel and cutting them off at the pass. Don’t look over there, she seems to say: focus. Some readers will find it challenging to pay such close attention in 2024 – but it’s thrilling, too, to be masterfully manipulated. The book is one thing and then it’s another, pushing the boundaries of narrative reliability, of plot, even of genre – but it’s managed so deftly there’s never a doubt that Wolhuter will pull it off in the end.

Shadow of Winter Robins by Louise Wolhuter is published by Ultimo Press ($34.99)