Teens are using 'aura points' to calculate coolness. The trend may reveal just how self-conscious they are.

Waving to someone who wasn’t waving at you? Minus 1,000 aura points. Throwing your garbage in the recycling bin versus the trash can? Plus 500 aura points.

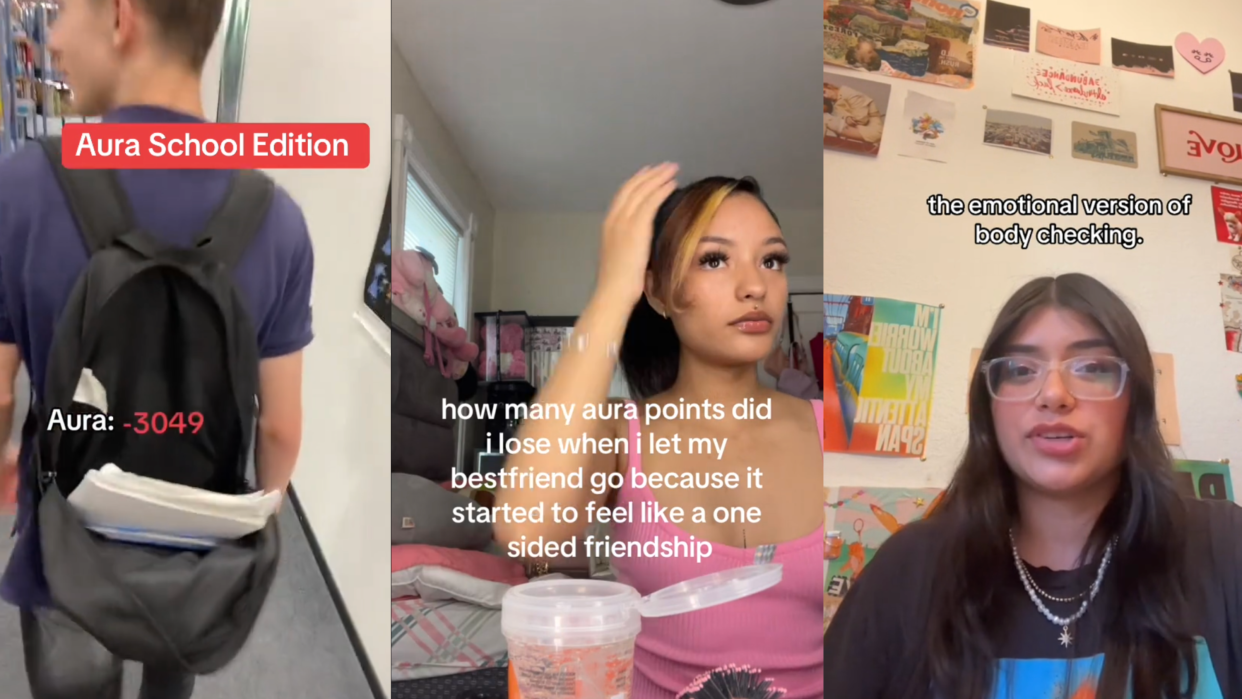

In a new social media trend popular among TikTok’s teenage set, users rank their cool factor (or lack thereof). How you gain and lose points varies greatly, as there are no set rules or official point system, and you’re the one doing the scoring. It’s all just “vibes.”

By putting their every move under a microscope and creating a made-up point system for each decision, young people can reclaim power over life’s cringy moments and redeem themselves in the eyes of their peers. But doing so could come at the cost of their mental health, experts say.

What are ‘aura points’?

High school student Sunny Grace, known on TikTok as @sunntie, recently shared the “worst ways to lose aura in school.” Her aura faux pas included twitching in class (-1,500 points), walking with your backpack open (-988 points) and falling up the bus stairs (-99999999 points). The video got more than 26 million views and over 13,000 comments, most from others sharing embarrassing aura deductions like “bumping into a desk when walking in the aisle of the desks” and “your stomach growling during a test.”

She followed up with instructions for how to “revive” aura after a long day of losing points. Points were accrued by acting mysterious in the hallway (+2500 points), executing the perfect dap up (+755 points) and tripping but saving it (+10,000,000 points).

Aura was first used as a ranking system of personality traits in a 2018 meme format, “weak aura vs. strong aura.” Listening to Apple Music revealed a weak aura, while using Spotify was a sign of a strong aura. In 2020, “aura” came to describe someone’s cool factor in a New York Times article about Liverpool soccer star Virgil van Dijk: “Van Dijk’s mistakes can be dismissed because, basically, he has an aura.” The word migrated to TikTok with a video about van Dijk posted in April 2023. The trend then evolved beyond the sports world to capture a certain X factor someone has (or doesn’t).

Now, the most common use of “aura” ranks everyday awkwardness.

In another version of the trend, referred to as “How many aura points did I lose,” TikTokers are asking others to assign aura points for them — but instead of low-stakes “cringe,” they’re sharing more serious experiences, like breaking up with a best friend or staying in a toxic relationship.

Experts weigh in

Esther Fernandez, the Gen Z face of the Made of Millions mental health nonprofit, compares aura to body checking, a compulsive form of examining and measuring one’s weight, size or shape. She worries that the trend, no matter the format, might be forcing young people to curate a “cool” version of themselves, leaving no room for authenticity.

Dr. Barbara Greenberg, a teen, adolescent, child and family psychologist, agrees. “I think it’s now become a socially acceptable way for teens to put themselves in the spotlight for praise or good-natured humor,” she says. “They get some sort of attention that they desire.”

According to Greenberg, it’s not yet clear how much extra pressure aura points put on teens — but the trend does reveal the inner workings of Gen Z and Gen Alpha. “The trend [reflects] how self-conscious teens are and how much they want to fit in,” says Greenberg. “My hope is that it does not lead to too much social comparison and an excessive amount of self-monitoring.”

Aura points may be adding stressors to an already stressful childhood and school experience, Jamie Cohen, digital culture expert and assistant professor of media studies at CUNY Queens College, tells Yahoo Life. “Like most trends, [aura points] will come and go, but this trend is basically an adaptation of social ranking to everyday life,” Cohen says. “Kids may prioritize how they’re being perceived over just simply being themselves.”

To Cohen, the trend feels like a way of making social ranking broader and more calculable — which has some dark implications. “The term ‘points’ suggests scorekeeping, so aura points could easily be called ‘aura ranking’ and then it gets really dystopian/Black Mirror,” says Cohen. This point system could lead to performative anxiety, feels Cohen, which could change participants’ way of interacting with the world.

“Being a kid and being weird and being awkward is part of growing up. ... Play and creativity are important parts of childhood, and the weight of aura points could negatively impact young people, especially vulnerable people who are developing their identity in real time,” says Cohen. “Parents should have discussions with children about this, reminding them they are perfect the way they are and aura points are just a trend.”

It’s not all bad, says Cohen, as it’s helping young people evaluate their worth. “Aura is technically the energy we give off, so recognizing that someone is sucking energy or aura away from you should be recognized as a negative thing and can be countered by preserving your aura with good intentions,” Cohen says. The trend could just be a lighthearted game among teens and their peers, Greenberg adds. “The teens who post are doing so voluntarily and seem to be having fun,” she says.