The Caretaker: Ian McDiarmid is superb as Pinter’s pathetic tramp

No disrespect to Harold Pinter’s many achievements, but had he stopped writing after The Caretaker (1960), his break-through hit, then – much as if Samuel Beckett had penned no further stage-work beyond Waiting for Godot (1953) – that would have been sufficient to have left an indelible mark, and a transformative influence, on post-war drama.

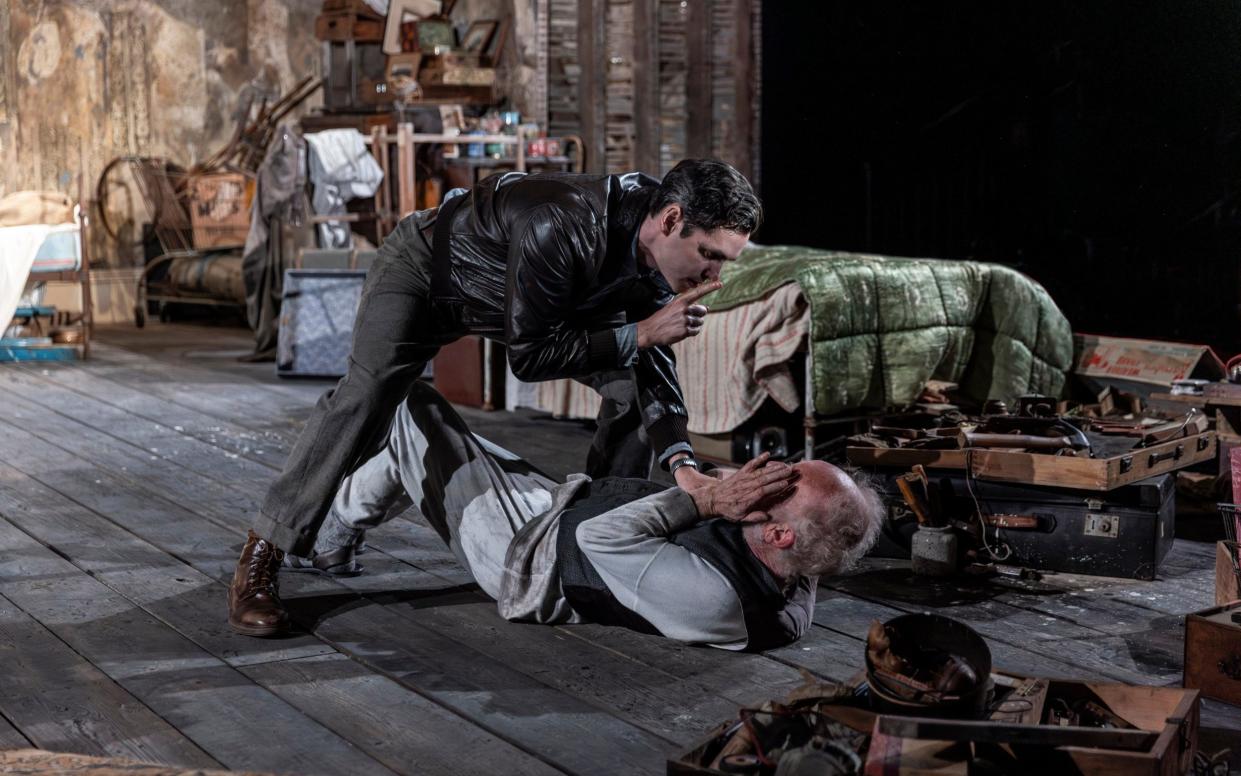

There’s such craft and concision to Pinter’s depiction of a triangular territorial battle in a run-down West London attic – involving an old tramp, the kindly, lost soul who invites him to stay, and the latter’s younger brother, who takes a less hospitable stance – that it still sets the bar inspirationally high. The play is both of its period and timeless, conveying the wider human condition in its tightly particular evocation of hardship and dispossession, its dialogue so wryly attuned to the way ordinary speech can be loaded and weaponised that it even got its own classification: “the comedy of menace”.

The central figure of the interloper Davies – akin to Beckett’s hobos but thrust into sharp-elbowed social reality – attracts heavyweights: in this century alone, Michael Gambon, David Bradley, Jonathan Pryce and Timothy Spall have brought their own traits and peculiarities to the part.

Justin Audibert’s beautifully paced (and, given our cash-strapped era, smartly timed) revival boasts Ian McDiarmid on superb form as the man who comes in from the cold. The Scottish actor is a past master at outsiders, most famously (the emperor) Palpatine in Star Wars. The fear was that, at 79, he might be too puffed-out for the part’s strenuous demands but he’s such a pro even indications of frailty seem like a theatrical tactic.

Designer Stephen Brimson Lewis delivers a scene of bare-bulbed, junk-cluttered domestic devastation; you almost fear for those treading its boards. For McDiarmid’s Davies, it’s a step-up. Still, he takes stock of his new habitat with a droll, beggars-can-be-choosy air of critical evaluation, arriving grimy of face in a large mac and outsized trousers, shoes in need of swapping for something unobtainably better. The accent and attitude – especially in the casual racism – is old-school cockney but not unwaveringly so, suggestive of a chancer who has been forced to accommodate himself to others’ inclinations for so long, he’s at once a chameleonic operator and a charlatan at a core, wretched level.

Besides his rich variety of behaviours – furtive, vicious, petulant and self-preoccupied, the smiles as mechanical as his anecdotes – there’s Adam Gillen’s slow and effortfully steady Aston, the brain-damaged prime occupant of the site, tinkering with electrics and fixated with building a shed. We take cruel relish in, and also wince at, the elaborate, deadpan wind-ups of his brother Mick (Jack Riddiford terrific with his heartthrob looks and flashes of heartless steel). But it’s Aston’s journey towards awkward self-assertion that delivers a necessary, hard-won sense of the bullied finding power, even in painful rejection. It’s a pity that Audibert adds stirring musical strains to this loner’s pivotal speech detailing his scarring psychiatric incarceration; when so much else is Pinterishly precise, even a small misstep feels like a major lapse of care.

Until July 13. Tickets: 01243 781312; www.cft.org.uk