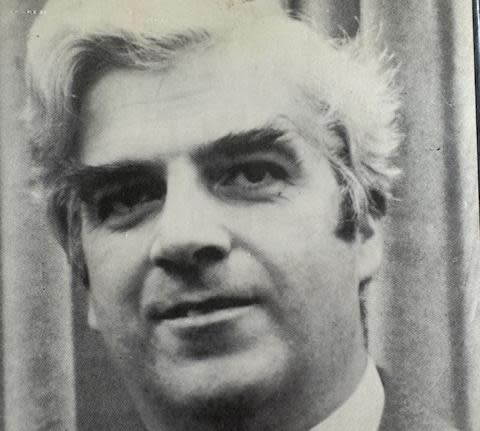

Ian Clark obituary

As chief executive of Britain’s smallest local authority, Ian Clark, who has died aged 85, went head to head with Big Oil in the 1970s to secure legislation to protect the Shetland Islands, which remains unparalleled to this day.

An evangelical Christian with an approach to negotiation that was compared unfavourably by one rueful Shell executive to that of Colonel Gaddafi, Clark unexpectedly found himself in the frontline of defence when Shetland was confronted with the North Sea oil boom.

With a population of just 17,500, the islands faced an immediate orgy of property speculation and a race among oil majors to develop and run their own terminals. Clark saw the imminent risk of unplanned chaos, which would result in the local economy and rich Shetland culture being overwhelmed.

Backed by some highly astute councillors, he decided that Shetland would need to acquire special powers from parliament to give the local authority control over developments and impose a levy on every barrel of oil coming ashore. To the fury of the oil industry, Clark was determined to push the extent of these powers to the limit and effectively veto onshore developments until they were secured.

While private legislation promoted by local authorities was not unusual, the powers sought by Shetland over the oil industry were exceptional. Critically, these included compulsory purchase of all relevant land and allowing the council to act as port authority and thereby concentrate oil coming ashore at a single, multi-user terminal at Sullom Voe.

This brought Clark into direct conflict with oil companies and speculators, backed by Edinburgh and London finance, who were already buying up land at highly inflated prices in key coastal locations. The approach also cut across local vested interests, and a bitter battle ensued with Clark and his allies steadfastly pursuing the legislative route to securing powers.

In March 1973, the ways and means committee of the House of Commons decided that the Shetland bill raised issues of such importance that it would have to go through a full parliamentary process. This put it into the hands of Jo Grimond, a former Liberal party leader who represented the constituency.

Grimond opened the second reading debate by saying that the bill “may well point the way to better methods of controlling developments consequent upon oil discoveries in other parts of Britain”. As far as Shetland was concerned, “the impact of oil on a rather unique island community will not go on for ever and may be over after 50 years … We must not sacrifice the long-term future of the community.”

By this time, Edward Heath’s Conservative government was desperate for infrastructure to be in place that would allow the first North Sea oil, from the Brent field, to flow. While it did not like Clark’s approach or the precedent that significant revenues would go direct to a local authority, it did nothing to stop the bill from becoming law in the spring of 1974, thus clearing the way for the construction of the Sullom Voe terminal.

Emphasis during the bill’s passage was more on planning powers than revenues. Shell had seriously understated the Brent reserves and only as the truth emerged about the volumes of oil that would flow through Sullom Voe did the extent of Shetland’s ongoing financial benefits become apparent.

The act had given Shetland powers to invest as well as spend. To this day, the funds hold around half a billion pounds, while vast sums have been committed to infrastructure and amenities over the past half century.

Grimond’s hope that Shetland would act as a model for the rest of Britain was not fulfilled. The incoming Labour government saw the attractions of the Shetland model, and when the British National Oil Corporation was set up in 1975 Clark left Shetland to become a full-time director with responsibility for setting up the headquarters in Glasgow, from where BNOC set about taking stakes in North Sea developments and investing overseas.

However, one of Margaret Thatcher’s first declared intentions after becoming Tory leader was to privatise BNOC and, fatefully, to deprive the UK of a state oil company. The process of dismantling it began with the part-privatisation in 1982 of the exploration and production wing, which was renamed Britoil and of which Clark became joint managing director. He retained this post until the whole lot was sold to BP in 1988.

Clark was educated at Dalziel high school in Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, the son of Alexander and Annie (nee Watson). He trained in accountancy before entering local government and was recruited to Shetland in the mid-60s as treasurer for what was then Zetland county council. With local government reorganisation in the early 70s, he became chief executive of Shetland Islands council.

After the demise of Britoil, Clark was much in demand for board positions with Scottish companies. Moving to live in Campbeltown, Argyll, in later life, he also had time to develop his lifelong interest in theology and in 2010 gained a PhD from the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. He was a lay preacher and contributed to religious, as well as professional, periodicals. In 1979 he had been awarded an honorary doctorate by Glasgow University.

Clark is survived by his wife Jean, whom he married in 1961, his son, David, and daughter, Susan.

• Ian Robertson Clark, local government officer and oil executive, born 18 January 1939; died 17 June 2024