Labour doesn’t deserve this lead

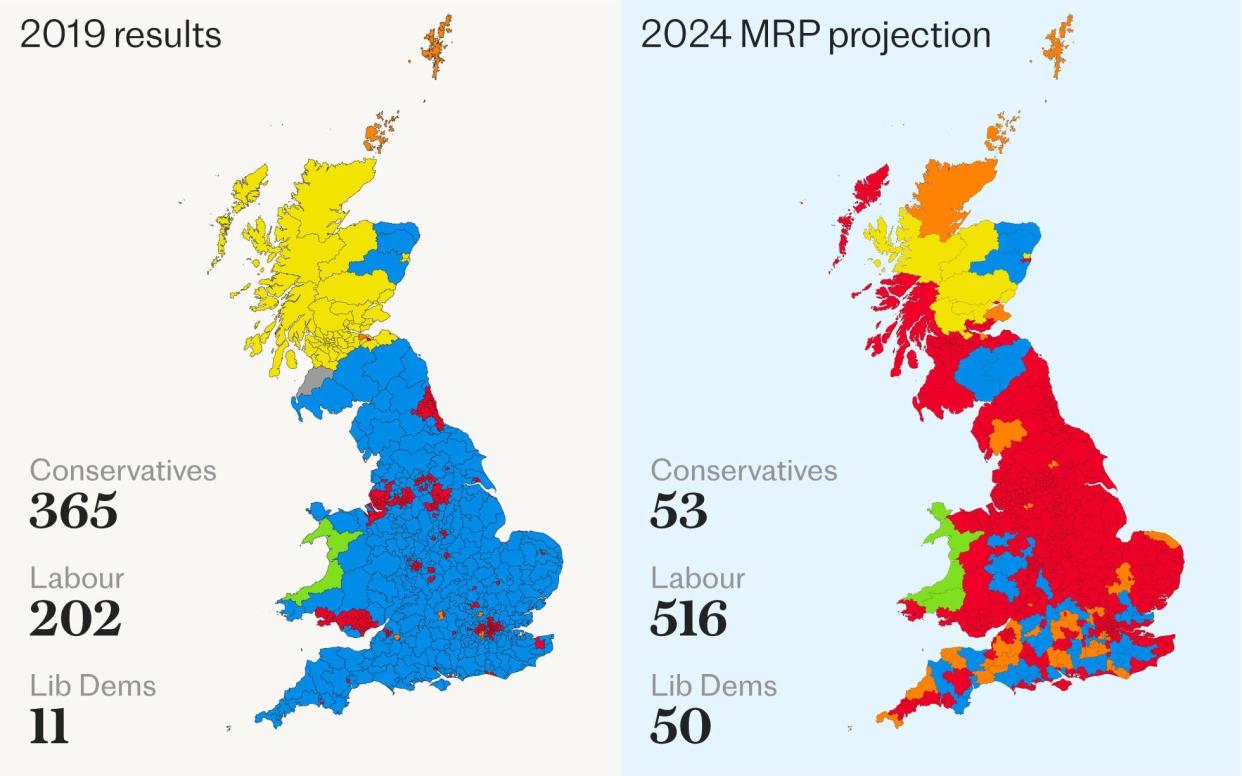

Our latest opinion poll makes for grim reading for the Conservatives. The Savanta MRP projections would leave just 53 Tories in the Commons and give Labour 516 seats. The Liberal Democrats would be just behind the Conservatives on 50 and within striking distance of forming the official Opposition.

To call this possible outcome unprecedented would be an understatement. It would be a shattering blow to the most successful political party the world has known. It took four elections, after Labour’s landslide in 1997, for the Conservatives to form another government on their own in 2015. After the calamity of 1906, when they won just 156 seats, it was another 16 years (and a war) before the Tories were back in office.

But to be reduced to double figures, with much of the current Cabinet losing their seats, would be a catastrophe. The Savanta projections even suggest that Rishi Sunak would lose Richmond in Yorkshire, the first prime minister ever to be ejected from the Commons in a general election.

This would be a so-called “extinction-level event” from which the Conservatives, as currently structured, may not recover without help from others on the Right, notably Reform UK. Indeed, it is the extent of support drifting to Nigel Farage’s party that is one of the main causes of this potential meltdown.

More than that, it is the Reform leader’s expressed purpose to destroy the Tories as a functioning political entity, though the poll projects that his party will fail to win a single seat, not even Clacton where Mr Farage is standing. The poll still shows the Tories well ahead of Reform in share of the vote, though some surveys have put them neck-and-neck.

We have been critical of many of the things the Conservatives have done, or failed to do, over the past 14 years. But the idea that they have been so uniquely awful that they merit their virtual destruction is absurd, as is the idea that Labour deserves such a huge majority.

Labour constantly attributes the political turmoil of the past few years to some inherent Tory defect when it was largely the function of unusual circumstances, beginning with the political upheaval of Brexit, and followed by the crises triggered by the Covid pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

It may be argued that the Conservatives should have handled these with greater acumen, but it cannot be denied that they were exceptional events. Brexit accounts for the ructions inside the party, Covid for the country’s deepening indebtedness, and Ukraine for the cost of living crisis. No governing party would have withstood even one of these without being shaken to the core.

The ill-starred administration of Liz Truss and the impact it had on the markets, forcing her resignation, was arguably the worst of all of these occurrences because it has fed a Labour narrative of “chaos”. The word was bandied around on the airwaves on Wednesday by Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, to persuade voters that Labour, by contrast, would usher in a period of calm and prudence.

Yet Labour is perpetuating a myth. When Mr Sunak and Jeremy Hunt took over 18 months ago, they steadied the ship, reassured the markets, and sought to rebuild the Tory party’s reputation for competent governance.

The inflation rate is now back to 2 per cent – the Bank of England target – for the first time since before Russia’s invasion; more people are in work than ever; real wages are growing once more; and there is effectively full employment, with nearly one million vacancies to fill. The economy is doing better than that of Germany or France. Indeed, all political incumbents in Western democratic nations are being punished by voters, as attested by the recent election for the European parliament.

However, under the first-past-the-post system, small percentage shifts in support can lead to dramatic losses. For the Tories, threatened on all sides, this can translate into dozens of seats they would normally have held.

Labour could conceivably win a majority above 350 yet have a smaller proportion of the vote than Jeremy Corbyn in 2017. On a low turnout, it could only have the support of about 30 per cent of the total electorate. This is hardly a mandate for “change”. Traditional Tories thinking of deserting the party on July 4 need to think long and hard about the consequences of doing so.