‘I’m ready for everything and I don’t care’: the man refusing to turn up at an Australian ‘colonial’ court

On Monday morning Jim Everett-puralia meenamatta, a Tasmanian Aboriginal elder, is due in Hobart magistrates court to face a trespassing charge after his alleged illegal protest in March against old growth logging in the Styx Valley of the Giants.

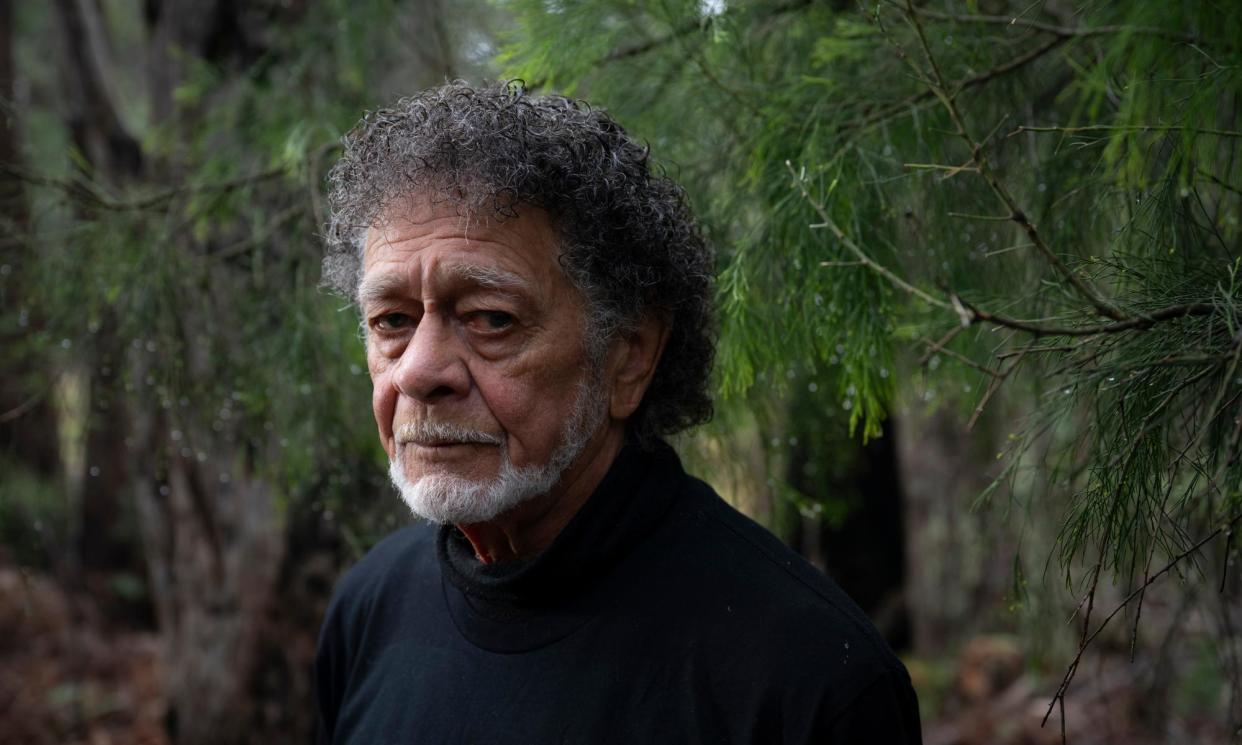

But Uncle Jim, as the beloved octogenarian Pakana Plangermairreener man is known, will be nowhere near the court. No, the celebrated artist, writer, academic and filmmaker will be as good as a world away at his traditional home on Cape Barren Island.

“I’ve got no intention of going to court,” says Everett-puralia meenamatta. He shakes his head and laughs.

Related: Tasmanian premier Jeremy Rockliff pledges to open protected native forests to logging

“Actually, you know, I’ll probably just be back home on the island until the day after I’m due in court. And then I’ve got to get back down here to Hobart for a meeting. They know me pretty well down here and I think they [the authorities] will be a little bit careful about what they do. If there’s an arrest warrant out for me after that, well I’ve just got to try to evade them for a bit. That shouldn’t be too hard.”

Regardless, he does fully expect, at some point, to be rearrested and charged with failing to appear on the trespass charges. He also anticipates the ultimate penalty could be a significant prison sentence or a fine of up to $45,000.

“She’s a big fine. But I’m a poor man. I’m an old man and a poor man. And I’ve got nothing that they can come and take off me that would worry me. So long as they stay away from my library.”

Everett-puralia meenamatta looks sprightly for 81 as he drags on a cigarette one cold morning outside his son’s home near Hobart. “I’ll be 82 later this year – and yeah, I’m in pretty good shape. I dunno what it is. It must be all the mutton bird oil, mate,” he says.

More laughter.

But for a man his age – even one in such apparent good health – the prospect of white man’s prison is probably no laughing matter. Likewise, the issues that Everett-puralia meenamatta is seeking to highlight by provoking the authorities to arrest – and rearrest – him.

In some ways what Everett-puralia meenamatta is doing seems profoundly simple: he wanted to be arrested at the Styx in March, and was. And he eventually wants to be rearrested for failing to appear in court – though not until September, because he plans to be involved in further protest action with friend and fellow Tasmanian activist Bob Brown, who has himself been arrested many times in the forests.

Here is where it gets slightly more complicated. Beyond his 50-plus years of environmental activism and protest against the wholesale destruction of Tasmania’s culturally totemic old growth forests, Everett-puralia meenamatta’s desire to be arrested and eventually rearrested – and perhaps jailed or fined – is strategically aimed to highlight issues of Indigenous sovereignty, legal jurisdiction, colonialism and the citizenship status of Indigenous people on this continent.

“I do not identify as an Australian citizen,” says the former commercial fisherman, who recently obtained his master’s degree in history at the University of Tasmania.

“There has never been a true conciliation between First Nations people and the colonial nation of Australia. And any notion that First Nations peoples are citizens of Australia is an historic political lie being maintained by governments and institutions alike.

“It’s a trickery throughout its history to evade any responsibility to negotiate a treaty with our First Nations.”

Everett-puralia meenamatta does not recognise the court’s jurisdiction over him, as an Aboriginal “non-Australian citizen”. The court, he explains, is like so many Australian institutions – an enduring colonial instrument of an Australian state he neither recognises nor belongs to.

“Of course I don’t intend to even go to the court [on Monday 3 June]. I mean that would just be giving them jurisdiction over me if I walked into the court in the first place. You can’t engage with the colonial court system because once you acknowledge that jurisdiction then how the hell can you argue that they’ve got no jurisdiction when you’re asking them to make a decision on your case?’’

Ideally, he says, he will avoid rearrest until September. But he’ll be easy for the police to find then, for the glorious Tasmanian spring marks the resumption of the logging – and protest – season. He will be protesting in the forest, attempting to disrupt logging, with many associated with the Bob Brown Foundation (including Brown).

“If I’m arrested then and forcibly taken into the court then I’ll be saying ‘You’ve got no jurisdiction over me because I’ve got a sovereign right to protect my country’ – not that I’ll be making a plea, understand, but I’ll be telling them that,” he says.

“The major issue I’m trying to highlight is the question of Aboriginal citizenship and I’m simply using the court and its jurisdiction as the political gateway to that.”

Everett-puralia meenamatta’s questions around the purported Australian citizenship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are deeply steeped in post-invasion history, not least in his island state.

“By the late 1830s they’d already decimated our people and they’d started putting us onto Flinders Island. The rest of us survived mainly on Cape Barren Island. So I am fifth generation [on Cape Barren].

“In 1876 when Truganini died they declared us extinct. So, they weren’t making any agreements or treaties with us or making us citizens or recognising us in any way because as far as they were concerned we were extinct. Then later they say we are citizens. They never asked us and we didn’t ever agree to that.”

Purported “extinction”, of course, was fallacious. Tasmania has thriving communities of descendants of survivors of what was an attempted genocide (an “apocalypse”) of traditional custodians.

Everett-puralia meenamatta’s point – one that might yet be debated by constitutional lawyers – is that the “colonial state of Australia” has not entered into any worthy agreement with a continental-wide representative body (a “Black government”) under which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people decided to participate in the Australian state as citizens.

And that is why he and some other Aboriginal people consider themselves not to be Australian citizens. He has written academic papers about this. It’s a question central to his master’s thesis.

All of this, he says, has profound implications for commonwealth treaty-making – an issue he believes will be up to the next generation of activists to pursue in a future he may not be a part of.

“To negotiate an [Australian commonwealth] treaty with us, we must firstly resolve the issue of citizenship. The government will not be able to prove that Aboriginal nations made any agreement to be Australian citizens and there exists no records to assert it.”

He says amid all of the talk by the federal government about truth-telling and future treaties “our status [when it comes to] our ability to negotiate treaties needs to be addressed”.

“Are we citizens negotiating a domestic agreement treaty under legislation of this country, or are we indeed talking about sovereign agreements?”

Other Indigenous people have challenged – albeit in different ways – commonwealth assumption of their citizenship. A decade ago Murrumu Walubara Yidindji (the Aboriginal journalist formerly known as Jeremy Geia) “quit Australia” while remaining on this continent, reverting to his traditional name and primarily to the law of his Yidinji people.

That – like Everett-puralia meenamatta’s rejection of Australian citizenship and refusal to acknowledge colonial institutions and legal jurisdiction – has its challenges, of course. Take, for example, when he was arrested back in March.

“When they got me out of the forest and into New Norfolk jail – the police station there … well I wasn’t actually locked up, they just took me in there and sat me down a chair while they did up some paperwork.

“And I signed the bail documents and got out. I didn’t intend to sign the bail documents. But I just forgot what I was doing! And my son later had a go at me about it.

“And I said, ‘Well it doesn’t matter does it? I mean if the colonial court system has no jurisdiction and I sign one of their papers just to get out of jail – well I’d sign anything just to get out of jail – it doesn’t give them any jurisdiction’. But I’ll be careful next time not to sign the bloody bail documents.”

Living on this continent as someone who does not accept Australia citizenship, recognise many of its institutions, legal sovereignty or jurisdiction, is a matter of constant negotiation – “of survival” – he says.

“You know, we are encapsulated in this colonial system too. You live in it. I live in it, just the same as the next person. You do it or else you bloody well die. It’s a matter of survival. If you don’t, then you don’t have an income and you don’t have a way to live. So, I’m caught up with it too.”

What will happen after Monday, when he doesn’t appear in Hobart court, let alone in September, post-anticipated rearrest?

“Who bloody knows? I’m ready for anything. And I don’t care.

“And that’s not the question. The question is: who can do it? I’m probably the only one that can because I’m an old fella, I’ve got no money and I’ve got a high enough profile to lift this into the public domain.”

One thing is certain: come Monday, Jim Everett-puralia meenamatta will not be fronting that “colonial” court in Hobart.