Scientists set sights on asteroid larger than Eiffel Tower as it skims past Earth

In 2029 an asteroid larger than the Eiffel Tower will skim past Earth in an event that until recently scientists had feared could foreshadow a catastrophic collision.

Now researchers hope to scrutinise 99942 Apophis as it makes its close encounter in an effort to bolster our defences against other space rocks.

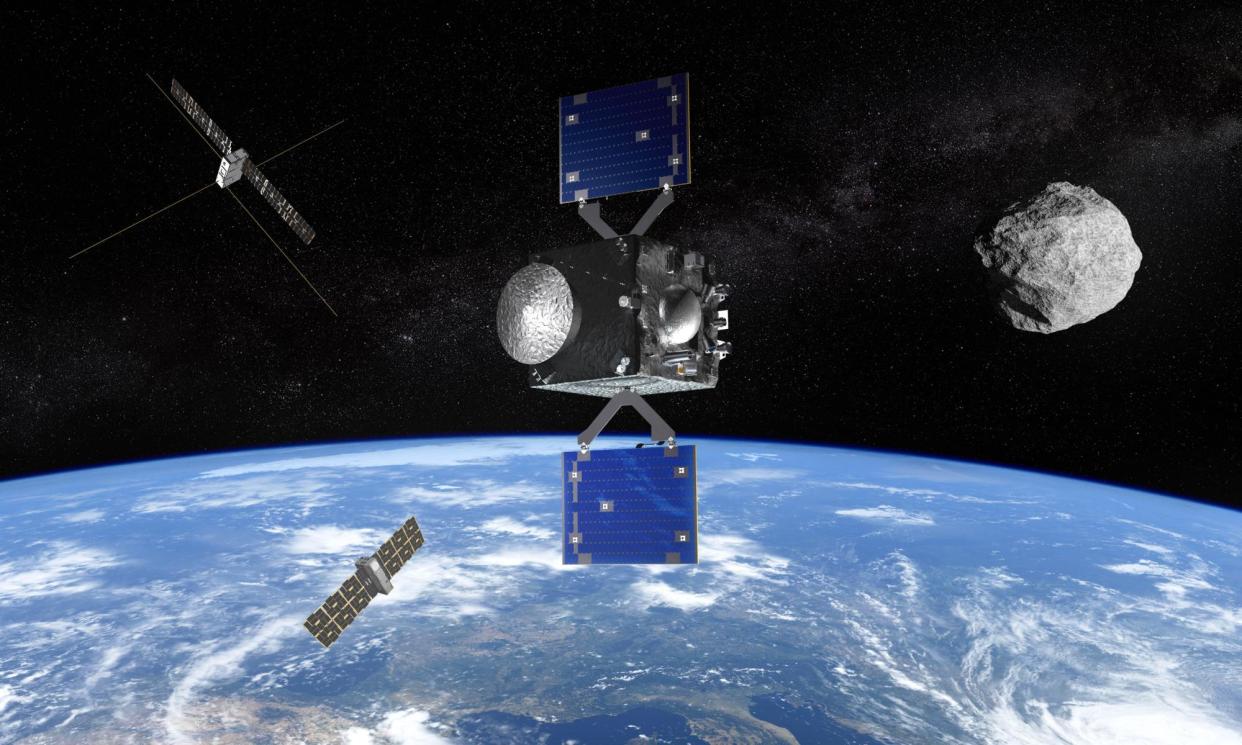

The European Space Agency (Esa) has announced funding for preparatory work on the Rapid Apophis Mission for Security and Safety (Ramses) in which a spacecraft will be sent to the asteroid to glean information about its size, shape, mass and the way it spins as it hurtles through space.

The mission will also shed light on the composition and internal structure of Apophis, as well as its orbit, and explore how the asteroid changes as it passes within 20,000 miles (32,000km) of Earth – about one-tenth of the distance to the moon – on Friday 13 April 2029.

“The flyby it does with Earth is absolutely unique,” said Dr Holger Krag, the head of the Esa’s space safety programme office, adding that no asteroid is expected to come as close for a few thousand years. “If the sky is clear, you should be able to see it with your naked eye.”

Apophis will pass closer to the Earth than the geostationary satellites used for TV broadcasting, navigation and weather forecasting. At that distance, Krag said, the asteroid would start to interact with Earth.

“It’s the gravity field of the Earth that will basically slightly reshape the asteroid, causing it to change its form,” he said, adding the gravitational pull could also cause landslides on the asteroid’s surface.

Krag said the insights from Ramses would help scientists understand the asteroid, and the risk such space rocks pose. “Our goal in planetary defence is not to do science on asteroids, but it’s to characterise them in a way that one day we can deflect them when they become dangerous,” he said.

Prof Monica Grady of the Open University said while most asteroids were in fairly secure orbits and did not come near our planet, Earth-crossing asteroids such as Apophis were a different matter.

“They come near the Earth, and there’s potential that one day one of them will hit the Earth and cause a major disaster. We believe this happened 65m years ago, when the dinosaurs were all wiped out,” she said. “And if it’s a big asteroid and it hits us, it’ll be a catastrophe which will destroy humanity.”

After its discovery in 2004, Apophis kept scientists up at night with concerns it might collide with Earth as it orbits the Sun. While Nasa ruled out an impact as Apophis approaches Earth in 2029 and 2036, it was only in 2021 that experts said a smash would be off the cards for at least the next 100 years.

However, space agencies are not leaving the security of the planet to chance, instead investigating ways of tackling Earth-bound asteroids.

Among such projects is Nasa’s Dart mission, in which a spacecraft was smashed into the asteroid Dimorphos to test whether it was possible to deflect a space rock. The Esa’s Hera planetary defence mission, due to launch this year, will study the aftermath of that crash.

“What the Dart experiment has shown is it’s very important to understand everything about the target asteroid before you impact it,” Krag said. “Because the composition of it matters, the spin rate matters, the mass matters. So, in principle, before engaging with an asteroid, you need to be able to do a very, very fast inspection.”

Ramses offered scientists the chance to practise just such a rapid reconnaissance , he added. “You cannot just go and hit [a target asteroid] because then you cannot predict the outcome. And you could make it worse.”

Prof Alan Fitzsimmons of Queen’s University Belfast, who is on the science advisory team for Ramses, said the data collected by the Ramses mission could also help scientists extend the window for which they could predict potential collisions with Apophis for many hundreds of years. “Our descendants at the moment still have to worry about this thing,” he said.

Krag said the new financing of Ramses would allow the team to buy the first hardware for the mission – although the final decision on whether Ramses would go ahead would not be made until the end of next year.

As well as carrying an Asteroid Framing Camera, Krag said other potential instruments could include a seismometer to monitor activity as the asteroid experiences Earth’s gravitational pull.

Should Ramses be approved, the plan is to launch the spacecraft in early 2028. “So we have a little less than four years, which is very rapid for a spacecraft,” Krag said.

Ramses is not the only mission preparing to scrutinise Apophis: after Nasa’s successful Osiris-Rex mission last year, which recovered 4.6bn-year-old chunks of space rock from the asteroid Bennu, the same spacecraft will rendezvous with Apophis in 2029 under a new mission title, Osiris-Apex.

While Ramses will arrive at Apophis before its close encounter with Earth, Osiris-Apex is expected to arrive afterwards.

Dr Terik Daly of Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, who is involved with the Osiris-Apex mission, said: “What Ramses is going to be able to do is to document Apophis prior to the asteroid’s close encounter with the Earth. So then [Osiris-Apex] can really look and see what did this natural experiment do. How did it change Apophis?”

Daly said the fixed date of Apophis’s close encounter with Earth was important. “There’s nothing we can do about it in terms of changing that date – and that’s what would happen in a situation where an asteroid was coming to hit the Earth. We can’t negotiate with the asteroid. What we can do is prepare to respond in an effective way.”

Grady said while such missions were interesting to scientists, they also held a wider appeal. “It’s very exciting as a member of the public to realise that we actually can do something about averting the Earth from a catastrophic extinction,” she said.