Sex and secrets in PM’s limo: Asquith’s wild trysts with socialite mistress

She was a young aristocrat who knew all the “best” people. He was an ageing politician leading a nation on the brink of international conflict. Yet their passionate weekly trysts in the back of the official prime-ministerial car changed the course of history.

Add the fact that our heroine was the closest friend of our hero’s daughter, and it reads like the tagline for a tale of forbidden love and secrecy in high places. But it happens to be true.

The bestselling author Robert Harris has discovered that Herbert Asquith’s adulterous Downing Street affair – routinely dismissed by historians as an insignificant dalliance or as mere platonic affection – was in fact the cause of both British military and political crises at the onset of the first world war. Against all protocol, it is now clear Asquith shared vital military secrets and coded documents with his paramour, the Honourable Venetia Stanley, compromising national security. He also failed to recall important strategic information about army ammunition supplies because he had given the key briefing document to Stanley, 35 years his junior.

“It has always been suggested this was more of a fantasy relationship than a real love affair,” said Harris this weekend, having unearthed fresh details while researching his new novel, Precipice. “But there are paragraphs left out of his published letters to her that indicate it was much more. He wrote notes to Venetia, then in her late 20s, during crucial cabinet meetings and clearly sought her advice, as well as sending her love poetry – lines from Tennyson and Browning.”

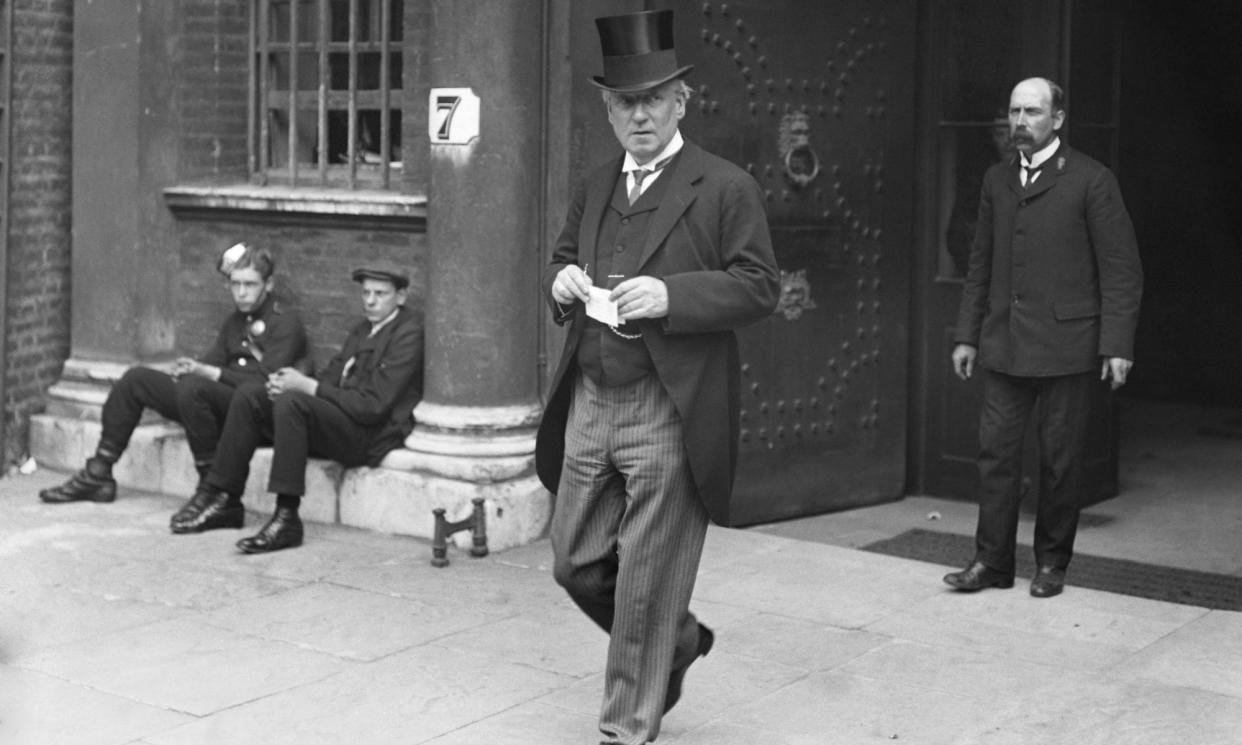

The Liberal leader, prime minister between 1908 and 1916, was known for writing letters to aristocratic women. When he met Stanley, a leading socialite, he was quickly besotted. At the height of their covert relationship, the married man and father to seven wrote to her three times a day and organised Friday afternoon drives in the sealed compartment of his state car, a 1908 Napier.

“I became fascinated by this aspect of Asquith’s story,” said Harris. “We can account for so much of his time in the run-up to the first world war, but this enabled me to tell that story day by day through the 560 letters Venetia kept.”

In his last days in No 10, having resigned and invited the Conservatives to form a coalition government after a fateful weekend in 1915 when he was unable to reach Stanley, Asquith is believed to have disposed of her letters. “He had a huge bonfire, but I could put together her replies, I realised, from what he had said and from the bits he quoted.”

The claim that the physical element of the affair has been underestimated, Harris believes, is supported by the fittings of the PM’s car: “It was not how we might imagine now. It was totally sealed, like a bedroom on wheels, with blinds on the windows and only a push-button intercom to speak to the driver.”

But sex is not the only missing component. Stanley and Asquith also discussed everything. “He enjoyed talking to her because she was clever and not trying to get a job or anything,” said the acclaimed author of hits such as Fatherland, Pompei and The Second Sleep. “So I feel that Venetia, like so many significant women behind the scenes, has been somewhat excised from history. If nothing else, I hope my novel will help give her the place she deserves.”

Stanley’s granddaughter, Anna Mathias, told the Observer she is “completely delighted” by Harris’s novelistic treatment. “As soon as he starts writing, you’re suddenly there in London in 1915. He brings my grandmother to life and makes her quite a heroic figure.” Mathias is also persuaded by Harris’s interpretation of the regular car journeys: “I grew up with an idea in my mind, but Robert has more or less convinced me that logistically it was entirely possible.”

Both Asquith’s wife, Margot, and his daughter, Violet, were dismissive of Stanley’s seductive powers, disbelieving the affair when it was later revealed because she was “so plain”. But Mathias thinks they misunderstood her appeal. “Political influence was pretty much the point of her. She was not frivolous. She was bright and articulate, although I have no doubt she played very fast and loose as well. She was pretty busy in the bedroom in her later life, I know. But I have the notes of what she read as a young woman: Dostoevsky in French and EM Forster’s novels as they were published.”

Her father, the fourth Baron Stanley of Alderley, was also unconventional, Mathias says: “They were toffs with an old title, but they were considered weirdos. He was leftwing and the first British peer to convert to Islam. As a child, Venetia was ridiculously indulged, with pets that included a penguin, a bear, a parrot and a monkey.”

Crucially for Harris, Asquith shared carbon copies of secret intelligence during the car journeys and then threw these “flimsies” out of the window. When a few were handed in to police in 1914 there was an investigation at the top of government. This incident gave Harris the inspiration for his narrative.

Mathias’s late mother, Judy Montagu, showed Venetia’s letters to Violet’s son, the publisher Mark Bonham Carter, in the early 1960s. A full typescript was made and shared with the politician and writer Roy Jenkins, who was commissioned to write Asquith’s biography.

But the PM’s descendants kept control over what was used, and the affair was downplayed. The biography, published in 1964, describes the heated correspondence as “both a solace and a relaxation, interfering with his duties no more than did Lloyd George’s hymn-singing or Churchill’s late-night conversation”. But Harris now knows that the PM once hoped to run away with Stanley and that when she broke off the affair in 1915 to marry his colleague, Edwin Montagu, he was deeply distressed, “bordering on a temporary nervous breakdown”.

Precipice ends with Asquith making the lonely decision to end Britain’s last Liberal government.